RW Johnson

The increasing threat posed by Ansar al Sunnah jihadists in Mozambique’s northernmost province of Cabo Delgado finally caused major international concern after the ISIS-linked insurgents attacked the town of Palms on March 24.

The Americans, the Portuguese and others offered military training to the hapless Mozambican army, which seems utterly incapable of dealing with the threat.

In addition, SADC leaders became alarmed at the thought of major foreign forces becoming involved in the region and at a summit in Maputo on April 8 they resolved to send a technical mission to assess the situation and recommend what sort of force seemed to be required.

So far, so good. But when the technical mission arrived in Maputo it was told that it could only spend a day in Cabo Delgado. Indeed, it became clear that the Mozambican government wasn’t keen for the mission to go to Cabo Delgado at all.

Ultimately the mission recommended that a force of 2,900 with four helicopters and some naval support would be required – a ludicrously inadequate force in the eyes of most military strategists. For Cabo Delgado is big – 82,000 km2 – with 16 district centres which would need to be secured from attack.

But Mozambique’s President Felipe Nyusi wasn’t at all keen. Indeed, ever since the crisis broke he has consistently opposed any regional intervention to help him, though he was happy enough to enlist the help of Russian and South African mercenaries (the Wagner and DAG groups).

A decision had to be made at the SADC security summit on April 29. On the day before that SADC foreign ministers unanimously adopted the technical mission’s report and said that Mozambique’s forces needed “immediate support”.

But President Nyusi was clearly determined to avoid such an outcome. He managed to engineer the “indefinite postponement” of the security summit, so the SADC leaders never met and the mission report was never ratified.

So here is a man whose house is on fire. The flames have reached a point where not only his regional neighbours are alarmed but where alarm bells are ringing in Washington, London and Lisbon.

It is a known fact that his own fire brigade (that is, the Mozambican army) is unequal to the task. Yet although Nyusi has procured the services of mercenary outfits also unequal to the task he seems determined to shoo away both the regional and international fire brigades which could put the fire out. What on earth, then, is going on?

To understand the situation one has to dispel any lingering romanticism about the “liberation movement” in Mozambique. In truth the liberation movements of Lusophone Africa have all gone not just to the bad but the very bad.

There is no need to say more about the Dos Santos regime which ruled Angola from 1979 to 2017, entirely in the interests of just one family, but there are still some Pan-Africanists who like to hero worship Amilcar Cabral of Guinea-Bissau.

The Cabrals were indeed good men (I knew Amilcar’s brother, Luis) but the fact is that, contrary to everything they had preached, Cape Verde broke away to become a separate country at independence and Guinea-Bissau became a narco-state.

Hero-worshipping the Cabrals is rather like being a devotee of Toussaint Louverture, the liberator of Haiti – as many Pan-Africanists still are – without bothering to notice the utter rottenness of the regimes which have ruled Haiti ever since.

Mozambique is no exception to this law of decaying liberation movements. The major point to grasp is that heroin has been Mozambique’s biggest single export for two decades and that the trade is increasing.

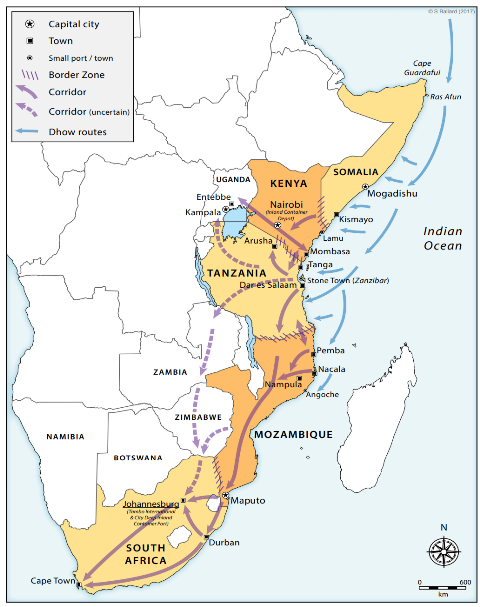

The heroin comes from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen, arrives off the northern Mozambique coast by dhow, where it is off-loaded onto smaller boats, warehoused in Cabo Delgado and then transported to Johannesburg by road.

If it is in a container it goes to City Deep Container Terminal, if not, it goes through O.R. Tambo airport – both destinations being notoriously corrupt – and is then trans-shipped to Europe (a certain amount of dagga and mandrax (methaqualone) also finds its way into the South African market).

The trafficking routes through Cabo Delgado are long-established. Mozambique has no navy or coast guards so effectively the long coastline of the Northern provinces are unpoliced. Not only drugs come this way – so do rubies, gold, timber, banned wildlife exports and, of course, there is a traffic in people. This was, after all, an old slave-trading coast.

The only (small) fly in the ointment is the French naval base on Mayotte, at the head of the Mozambique channel which not only exercises maritime reconnaissance down the East African coast with its ships and planes but also includes a small Foreign Legion detachment.

Thus far, however, while the French have harassed the drug trade a little, they have shown no interest in getting more heavily involved.

The reason why Mozambique has achieved such central status in the drug trade is simple. The drug enforcement agencies of the developed world have made access to their markets difficult and dangerous so the drug syndicates have sought new and ingenious back doors into them.

Mozambique works well because northern Mozambique is as wild and unpoliced as anywhere on the planet and the country’s ruling elite is fabulously corrupt, making deals easy.

Even better, Mozambique is next door to South Africa which is not a hard drug producer, still has easy access to the developed world and is equally susceptible to corruption. This magical combination is, of course, what attracted the Guptas and many other criminals to South Africa.

Traditionally the heroin trade in Mozambique has been controlled by a small number of Muslim Asian families, most notably Mohamed Bachir Suleman, named in 2010 by President Obama as a “drugs kingpin”.

From the very beginning this trade operated under the protection of the Frelimo leadership which has reportedly pocketed millions a year from it. Suleman is probably Frelimo’s biggest donor.

The relationship between Sulemann and Frelimo began under President Joaquim Chissano (1986-2005). Chissano had been Frelimo’s head of security since 1966 and was thus ideally placed to ensure the compliance of the Mozambique security forces.

When Mohamed Suleman’s second son was married at a 10 000-guest wedding in 2001, Chissano was the guest of honour. (The parallels with the Gupta wedding in Sun City, attended by members of the ANC elite, are obvious.) Thereafter the business arrangement was handed on to Chissano’s successor, Armindo Guebuza (President 2005-2015). Guebuza, Mozambique’s wealthiest man, is known as “Gue-business”.

Thanks to this set of arrangements, the trade proceeded smoothly. Indeed, Frelimo carefully regulated the trade – it didn’t want the heroin to be sold in Mozambique and it didn’t want the trade to be visible to the country’s aid donors.

So there were no drug wars between the drug-trading families, no arrests, no convictions and no seizures of the heroin passing through. The police, the customs and Frelimo leaders all took their cut. With heroin reaching up to $300 million a tonne in Europe and up to 40 tonnes a year coming through, the trade was worth a cool $1 billion or more.

Since 2020 the heroin trade has been powerfully supplemented by methamphetamine, also coming from Afghanistan – so much so that by 2021 drug shipments in the dhows were up to 50 percent meth.

Some of this has found its way onto the South African market, but it has to be stressed that heroin traders are really looking for numerous and wealthy populations able to pay their top-end prices. This means that they really want to get their merchandise to Europe, Australia and the USA.

Since 2017 large quantities of cocaine have also been reaching Australia from South Africa (Australia and New Zealand have the world’s highest prevalence of cocaine abuse.). Indeed, in 2017-2018 Australia received nine times the volume of cocaine by air cargo from South Africa than from any other country.

Moreover, cocaine has been cropping up in container shipments from South Africa. In 2019 68kg of cocaine was found in a furniture shipment from South Africa and in another seizure 384kg was found. The large size of these shipments suggests that the South Africa-Australia route is regarded as safe and reliable.

The rise of the cocaine trade signalled a major change. The heroin came from Asia but the coca plant grows exclusively in Latin America, so this signalled that Latin American drug cartels were now getting involved too. Probably the key was the trade agreement signed in 2015 between Mozambique and Brazil.

This greatly facilitated the import of containerised goods from Brazil and pretty quickly some of those containers were carrying cocaine. Again, the intention was to route the drug through Mozambique, Malawi and South Africa to final destinations in Europe, Australia and the USA.

This naturally captured the attention of the American authorities and in October 2018 Tanveer Ahmed, a Pakistani drug kingpin, was arrested in Mozambique thanks to an operation led by the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Ahmed ran a major network in Mozambique dealing in heroin, cocaine and hashish. In 2020 he was extradited to the US.

This was followed in April 2020 by the arrest in Mozambique of Gilberto Aparecido Dos Santos, a really major Brazilian drugs boss linked to the Primeiro Comando da Capital (First Capital Command), Brazil’s biggest and most powerful organised crime group.

Dos Santos, who had been on the run from the Brazilian police for over twenty years, was accused of controlling a large-scale trade in cocaine and arms with ramifications throughout Latin America. He had apparently acquired bases in both Mozambique and South Africa.

Dos Santos was arrested, together with two Nigerian associates, at a Maputo luxury hotel in an operation in which the Mozambican police co-operated with the Brazilian federal police and, once again, the DEA. Dos Santos was immediately extradited to Brazil – the Brazilian air force sent a special plane to Maputo to pick him up.

The arrest of major druglords like Ahmed and Dos Santos was very much not the Mozambican way of doing things. In all previous time it could have been taken for granted that men like them would have paid off the Mozambican police, made handsome gifts to the Frelimo leadership and then gone happily about their business. What had changed these cosy arrangements was clearly the arrival on the scene of the DEA, an agency used to getting its way, with powerful back-up from the US authorities.

Moreover, everything had changed as a result of the discovery in 2015-2016 of the $2 billion in secret loans organised by Guebuza. Aid donors were furious at the deliberate falsification of Mozambique’s accounts.

They cut their aid to support the Mozambican budget, causing a major financial crisis; made it clear that Guebuza had to go; and in general began to wonder what other scams had been practised upon their naive goodwill. In this new climate of distrust the drug trafficking – which donors had hitherto benignly ignored – stood out as another major scandal.

It was in this climate that Felipe Nyusi came to power in 2015. Guebuza, in classic African style, had been busy trying to amend the constitution so as to give himself a third presidential term but all thought of that disappeared once Mozambique defaulted on its debts due to the loan scandal.

Quite clearly Nyusi needed to take his distance from Mohamed Suleman and other known druglords and, publicly at least, to deplore the drug trade and at least appear to support international efforts to disrupt the trade.

On the other hand the drugs trade had become one of Mozambique’s biggest and most lucrative exports and it provided a large and steady hard currency income for the Frelimo elite. There was simply no way that that elite would tolerate the cutting off of that income source: in effect it had become as addicted as any junkie.

So it was a basic condition of Nyusi’s presidency to hold the balance so as to appease the DEA and the aid donors on the one hand, but ensure that the Frelimo elite kept getting its fix, on the other.

If one now looks at the geography of illicit trade off the East African coast (see map) one can see how the increased pressure exerted by the Kenyan and Tanzanian governments on the old trading centres of Zanzibar, Mombasa and Dar-es-Salaam has forced a southward shift of focus.

The two key ports in this new dispensation are Pemba in Cabo Delgado and Nacala in Nampula province. Nacala has the deepest port in East Africa while Pemba has a container trade and its great appeal is that it is so far north as to be beyond the surveillance of anyone based in Maputo.

In 2010 Celso Correira, principal of Insitec Ltd. – described at the time as “a Guebuza front company” – took over management of Nacala port. Correira subsequently acted as presidential campaign manager for Nyusi and is currently Minister for Land and Rural Development.

Moreover, once the management of ports was privatised under Chissano, a solitary exception was made for Pemba which remained under the state ports and railways company, Portos e Caminhos de Ferro de Mocambique (the CFM). This was a very deliberate step by the Frelimo leadership to keep control of this ultra-sensitive centre of the drug trade.

All these delicate and sensitive arrangements were, however, threatened by the irruption of the jihadist insurgency in Cabo Delgado from 2017 on. As yet there is no evidence that the insurgents are involved in the drug trade though it is generally assumed that this is just a matter of time simply because that is the transactional way in which Mozambican politics works.

That is to say, after a brief period of revolutionary rhetoric the Frelimo elite settled down to enjoying all and more of the privileges the Portuguese had had. In the Renamo vs Frelimo wars that followed Renamo did not dwell on Frelimo’s corruption for, of course, the struggle was really about what share in the profits Renamo might obtain. The jihadists, too, are bound to want their share. The insurgency needs money. When they took Palma the insurgents robbed all the local banks.

The insurgency by Ansar al Sunnah is, of course, a huge problem to Nyusi and Frelimo. For years now Frelimo has been salivating about the mega-profits to be derived from the huge new gas finds – indeed, Guebuza’s $2 billion in secret loans were based on the assumption that he would get the money back from gas receipts and no one would ever know of the hole in the accounts. (In fact half of that $2 billion has never been accounted for.) So Total’s decision, in light of the murderous insurgency, to invoke force majeure and pull out is a tremendous blow.

This, then, is one explanation for President Nyusi’s otherwise baffling reluctance to welcome foreign military help against the jihadist insurgents in Cabo Delgado. From the moment the insurgency began and it became clear that the Mozambican army couldn’t cope with it, it has been a key objective for Frelimo to keep foreign forces away from this nerve-centre of the drugs trade.

Once SADC troops, let alone American, Portuguese or others, began roaming around Cabo Delgado they would inevitably discover what was going on, international journalists would expose it and, heaven knows, the foreigners might disrupt the trade or even take a slice of it for themselves.

All of which is unthinkable and the Frelimo elite will clearly not tolerate a president who allows this key source of income to be cut off. Meanwhile academics, journalists and aid workers are all forbidden access to Cabo Delgado. The journalist Tom Bowker was recently deported because he had wanted to report on the insurgency. Just to make sure that other journalists don’t start wandering around Cabo Delgado, Bowker’s deportation notice bars him for ten years.

So Nyusi first called in the Wagner group and then DAG, for he knew that neither the Russians nor mercenaries in general, would lose any sleep – or make any fuss – over the drug trade. Such dogs of war expect Africa to be venal, brutal and cynical. But gentle souls like Cyril Ramaphosa or Botswana’s Mokgweetsi Masisi would be shocked – one can almost hear Ramaphosa saying “I was shocked, shocked” – while if the Americans got involved they would doubtless bring in the DEA. It didn’t bear thinking about. This is why Nyusi has successfully dragged his feet and headed off SADC intervention for now.

For the moment the matter rests there. The trouble is that Ansar al Sunnah will not go away and already they have chased away enormous foreign investment. This is bad for the entire southern African region for it gives foreign investors the impression that however inviting the opportunities may be, the risks in this neighbourhood are simply prohibitive. Moreover, the DEA is now involved and doubtless understands the situation well enough. Huge trouble is waiting at only one remove.

Like most African politicians Nyusi is interested in really short term crisis management – the option to choose is whatever will keep the money flowing and put the trouble off for a few weeks, maybe even a month or two. But watch this space. – PoliticsWeb