Farai Mabeza

Zimbabwe’s debt crisis has contributed heavily to the collapse of the education system in Zimbabwe as it is squeezing out available public resources which could be benefiting the sector, a coalition of civil society organisations has claimed.

The acting national co-ordinator for the Education Coalition of Zimbabwe, Clemence Nhliziyo, said this in a presentation at the Zimbabwe Annual Multi-Stakeholder Debt Conference hosted by African Forum and Network on Debt and Development (AFRODAD) and Zimbabwe Coalition on Debt and Development (ZIMCODD) in Bulawayo recently.

Nhliziyo said debt had, among other things, led to the increased privatisation of education due to the poor resourcing and in some areas the unavailability of public schools.

As at the end of 2019, total public and publicly guaranteed external debt was estimated at US$10.6 billion (49% of GDP) while about 57 percent (US$6 billion) of the outstanding external debt are arrears.

“Debt drains impoverished countries of resources that could otherwise be spent on vital public services including education. Actors in privatization have ranged from powerful high net worth individuals and companies to average citizens trying to get a piece of the cake that comes with providing these services

“In Zimbabwe it has led to the mushrooming of backyard schools in most of the high density suburbs whose quality of education is highly compromised,” he said.

A research paper published by ActionAid in April this year indicated that 78 percent of countries with available data were advised by the International Monetary Fund to freeze or cut public sector wage bills in the past three years and Zimbabwe is among those countries.

Teachers are the largest group on the government wage bill so these IMF targets cannot be met without blocking recruitment of new teachers.

The impact of COVID-19 on education has also brought the debt crisis debates on the global agenda while, locally, schools have failed to reopen after the novel coronavirus-induced lockdown with teachers remaining at home demanding higher wages.

This is just one of the problems the sector is grappling with.

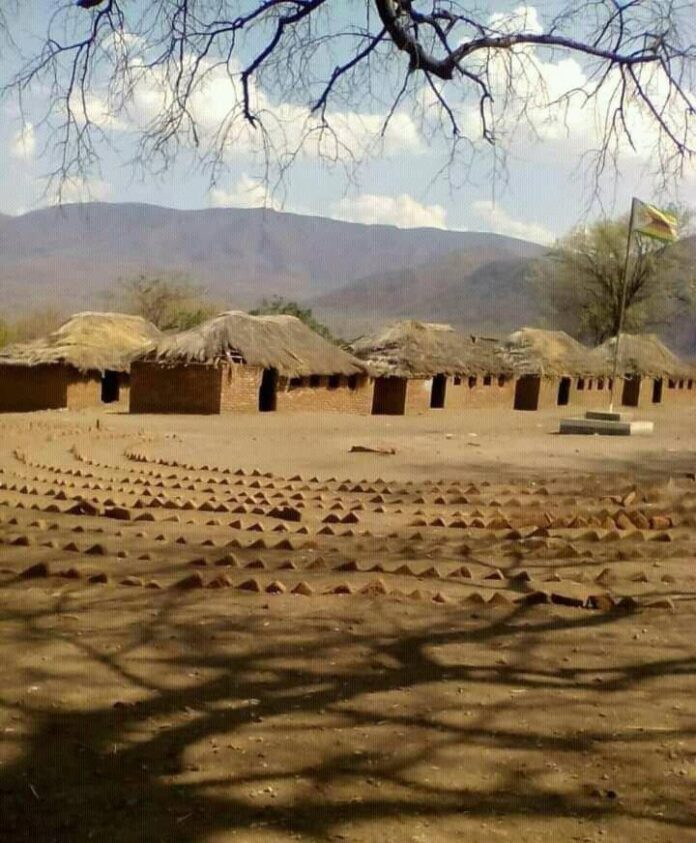

Poor infrastructure at schools means that children are crammed into overcrowded buildings, often without desks, making learning almost impossible and contributing to very high drop-out rates.

Zimbabwe has a high pupil-classroom ratio of 60:1 for ECD (national average) against the recommended 40:1 while the qualified teacher-pupil ratio is also too high especially at ECD with 1:66 (national average).

High cost of education has led to high dropouts (34% Primary and 45% at Secondary level).

More than 90 per cent of the education budget is spent on recurrent expenditure (43% in 2020).

“Therefore schools are largely reliant on private sources (fees and levies) and external support (donor aid) for capital expenditure,” Nhliziyo said.

Globally, debt is contributing to a failure to realize hundreds of millions of children’s right to a basic education, with wide-ranging effects.

Countries with a well-educated population are better able to fight poverty, sustain their people, and recover from conflict or natural disaster.

Children who complete primary school have far better chances of escaping poverty and crime, avoiding HIV and AIDS infection, and growing up to have healthy children of their own.