The imperial makings of a local/national currency in colonial Zimbabwe: Money as a product of imperial and colonial politics and law; 1930-1940

Tinashe Nyamunda

The Brookings Institute’s Economics Professor Steve Hanke has argued that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) has become a white elephant. He has suggested that it would be better for the country to operate using a currency board. Many in Zimbabwe have accepted his suggestion without a full appreciation of the political, historical and economic context in which currency boards were established in Africa.

Duncan Rowan has noted that the “standard type of currency authority in British colonial territories [were] currency boards”. These were established in West Africa between 1912 and dissolved in 1965, the East African Currency Board was in operation between 1912 and 1965, the Malayan Currency Board from 1938 to 1967 and the British Caribbean Currency Board between 1950 and 1957. The Southern Rhodesian Currency Board (SRCB) was established in 1938, renamed the Central African Currency Board in 1954 and succeeded by the Reserve Bank of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1956.

Each of these boards issued currencies on Britain’s behalf, to a group of colonial territories. In West Africa, the scheduled territories included Nigeria, Gold Coast and Sierra Leone. The countries covered by the Malayan Currency Board include what is today independent Malaysia and Singapore. In the Caribbean, the territories were Antigua and Barbuda, British Guiana (now Guyana), Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. In East Africa, the countries covered were Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda. In Central Africa, Southern and Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland made up the three territories of the SRCB. Given the suggestion by Hanke that the best interests of the Zimbabwean economy are to be found in an institution such as a currency board, this article looks at the context and history of the origins of local currency making. It examines the colonial currency board system of British imperialism and in part, the efficacy of Hanke’s suggestions.

In previous articles in this series, I have examined the consistent challenges that the colonial state and economy faced with regards to currency supplies. Even though, as Historian Antony Hopkins has argued, “[t]he interests of leading western nations [such as Britain] lay in ensuring that currencies of countries engaged in international trade were soundly based, readily convertible and … compatible” with the British gold standard to conduct smooth international exchange, the beneficiaries of these arrangements were not colonies. If anything, the colonies struggled, for reasons not least related to coinage supplies and challenges in the monetisation process, to adapt to this situation. Within Southern Rhodesia (colonial Zimbabwe), this problem persisted until the 1930s.

The colony had tried to have a Bank of Issue established from 1898, but by 1907 had failed because Britain refused to give her assent. I have noted in previous articles, that this was because Britain wanted to retain control of the functions of international sterling by managing colonial currency while allowing the white settlers in the colonies to utilise the system to accumulate wealth on the backs of African labour. But by the 1930s, even the settler community could not sustain accumulations under conditions of currency supply bottlenecks.

In a study of the origins of the SRCB, Historian Admire Mseba noted how, despite earlier calls of currency autonomy, white settlers were however not so inconvenienced by the issuing of British and South African currency which were the main markets for Southern Rhodesian products. But this was only if parity was maintained between the two currencies. But because of the global depression that started in 1929, the ensuing economic crisis upended this balance and affected the Southern Rhodesian economy. Having faced a number of challenges that led London to suspend the gold standard between 1915 and 1925, the British abandoned this system altogether in 1931 and depreciated (devalued) sterling. However, South Africa which had achieved dominion status and was no longer strictly a British colony, used its Central Bank (established in 1919) to remain on the gold standard until 1932, but retained the value of its currency. This created an environment of currency speculation, not unlike today’s black market trade in currencies in which some traders saw an opportunity to profit from the currency disparities at the expense of everyone else.

These currency disparities resulted in the hoarding of South African silver coins in Southern Rhodesia and their exportation into South Africa, creating a severe liquidity crisis not very different from the one experienced in the post GNU period in Zimbabwe and which still persists today.

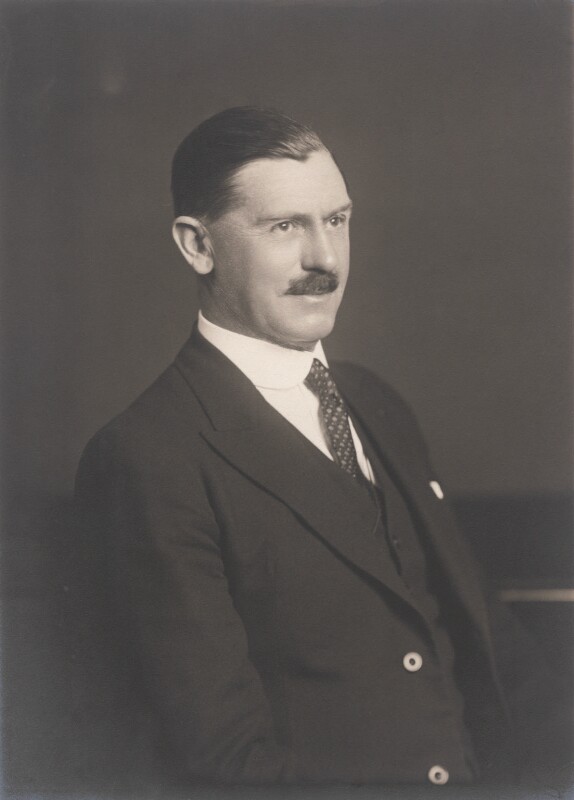

The consequent dislocation of commerce became an important political issue that resurrected calls for the establishment of a local currency and an authority to manage it. The white community that held the franchise became increasingly disaffected by the failure of the Rhodesia Party to make progress on the currency issue. Under Charles Coghlan’s premiership until 1927, Howard Moffat between 1927 and 1933 and the man who changed the title of the main political office from Premier to Prime Minister (also becoming the shortest serving Prime Minister in the country’s history), George Mitchell, the Rhodesia party successfully purchased the colony from the British South Africa Company (BSAC) at the cost of £2.3 million following the referendum to attain Responsible Government rule (or limited self-government). But because they opposed either joining the Union of South Africa or any sort of amalgamation with Northern Rhodesia, support for them waned. Another contentious political issue that was manifested by the challenges of the depression was the Rhodesian Party’s failure to secure more currency autonomy from Britain.

An opposition party, the Reform Party, led by Godfrey Huggins emerged to challenge the Rhodesia party and campaigned on the basis of unifying the two Rhodesias, and pursuing dominion status which would allow them autonomy to, for instance, establish independent monetary autonomy. In fact, Mseba notes, in its 1932 congress, the Reform Party proposed to create a reserve bank to issue currency and control the colony’s bank credit for the benefit of the white political constituencies of the colony. Under this mounting opposition, the Rhodesia Party pressured Britain for currency reforms. Ultimately, London assented to the passing of the Coinage and Currency Act (1932). This legislation lay the groundwork for the creation of colonial currency under conditions of Britain’s choosing.

Rhodesian coins would be minted by the Royal mint for a small seignorage fee (the difference between the value of money and the cost of producing and distributing it) and any notes would be printed by Bradbury and Wilkinson (private) limited of London. Under this Act, South African coinage was demonetised, and the colony’s new currency would circulate alongside British currency, not just at par, but under full imperial backing. In other words, the new currency was Rhodesian in name only but sterling in practice. Even as it was issued to appease the local settler political constituency, it was fully controlled by Britain in a way that maintained fully convertibility with sterling.

The new currency went a long way in eliminating shortages of currency, but it still had to be transported from London. It must be noted that while there was sufficient settler representation in parliament during the debates leading to the passing of the Coinage and Currency Act, Africans were never consulted and were viewed as peripheral to the whole process. The Southern Rhodesian economy became, for all intents and purposes, a settler economy. The ruling elite and its settler constituency secured a significant control of the local economy that can arguably be contrasted to that which ZANU PF and its closest elites have established. While in the context of the settler economy, the racialised economic system benefited the white settlers, it also developed the vision of a well-developed white man’s country they sought to establish. In this setting, white men were at the top of the food chain while Africans served as its cheap labour base. The post-colonial state has, in some ways, taken the form of negative neo-patrimonialism in which political elites, their patrons and syndicates are at the apex where they reap extractive benefits at the expense of the majority of Zimbabweans. The consistent connection there is the sustenance of primitive accumulation of capital.

In the short term, the Coinage and Currency Act (1932) partially corrected skewed currency dynamics. But it wasn’t enough to save the Rhodesia Party from electoral defeat in the 1933 elections in which the Reform party emerged victorious and Godfrey Huggins became the longest serving Prime Minister in the country’s history between 1933 and 1953, after which he became the Prime Minister of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland until 1957. In 1934, he facilitated a coalition between the Reform Party and the Rhodesia Party to create the United Party. But because of a mixture of interests, as well as British imperial interests, Huggins failed to secure a Reserve Bank and ultimately opted for imperial preference. But although Southern Rhodesia had its own currency, shipment and other logistical challenges caused inconveniences. In the end, Huggins demand for a currency institution resulted in the drawing up, passing and royal assent of the Southern Rhodesia Currency Board Act (1938).

Under this Act, a board would be established to oversee the issuance of the colony’s currency. But it is crucial to examine the currency board strategy more broadly than just from the context of local colonial politics. After all, among the main controls of the British sterling system was, as Economic Historian John Carland has shown us, its currency board system. The locus of British decision making in its colonies was its colonial office and its currency system which were both mediated in sterling and managed by the Bank of England. All of the foreign exchange reserves and gold of the colonies were held in London and any currency legislation had to pass through the colonial office for Royal Assent. Within the colonies, particularly in Southern Rhodesia, political power rested on the ability of the politicians to negotiate better concession with London, but ultimate hegemonic control of the colony’s economy through the use of sterling, fell on London which controlled sterling markets.

This takes us back to the beginning of this article, vis a vis the argument by Steve Hanke that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe is a white elephant and the country is better served by the mechanism of a currency board. While I don’t disagree that the RBZ is a corrupt and wasteful institution too big to be effective and so badly run than it is a liability rather than asset of the country, I also disagree that a currency board would be a more appropriate institution for Zimbabwe.

Currency boards, as we have seen here, are historical products of European imperialism that were created to serve the direct extractive interests of imperial centres. Similar to areas such as the Franc zone in Francophone Africa, Britain retained direct colonial currency links to its colonies as a way of maintaining economic control and directing the developments and the kind of production for its primary benefit, with African colonial subjects as the labourers in its African Empire. Currency played an important role, with colonial policies imposed through the violently attained claim to rule (right of conquest) as the avenue on which an international economic system was founded. Although, as subsequent articles in this series will show, there were global changes that shifted the terrain and balance of power in the aftermath of the Second World War, it is the legacies of such currency arrangements under sterling and institutions such as currency boards that facilitated the kind of economic dependency that persists to date.

If a currency board was to be established in Zimbabwe, which currency would be issued? Whose interests would it serve, and which monetary policies could possibly be followed under such an arrangement? In the case of colonial Africa, at least, currency boards meant that economic sovereignty was seized by imperial centres which then determined how colonial economies would be managed. Adopting such an institution in independent Africa would be surrendering the capacity to issue a currency and control national economies. I don’t disagree that African economies face numerous challenges under national reserve banks today, but there are alternative solutions, not least of which may involve African economic integration and creating, after careful consideration and well-informed research, currency areas if only political will were to be attained.

This article has examined a further stage in the making of a local currency in Zimbabwean history. This colonial currency was directly linked to sterling, making it, I argue, practically sterling despite taking the currency name of Rhodesia. These arrangements would be maintained until 1965 when Southern Rhodesia was expelled from the sterling area following its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain in 1965. But in the period between 1930 and 1940, Britain had deepened its control over the colony’s currency and economy in ways that expanded the benefits to the white community of Southern Rhodesia who now held the vast majority of agrarian and mining land and controlled mainstream commerce and industry at the expense of the African communities. After all, having purchased the colony from the BSAC at just £2 million, the Rhodesia Party government felt that it had politically secured the right to direct colonial development, even with a measure of British oversight, in ways that would benefit their racial constituency.

But the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 and the dynamics of global hostilities until 1945 would change the global economic terrain in ways that would trigger the retreat of British imperialism in ways that were, at the time, unexpected. This would activate changes in the global balance of power in ways that would accelerate the emergence of the United States of America as a superpower, leading to dynamics that would influence the direction of Southern Africa’s colonial political and economic development.

Watch out for next week’s article to see how these developments led to the beginning of shifts in colonial Zimbabwe’s economy and currency as the series continues.

- Tinashe Nyamunda is in the African Modernities Past and Present Research Group at North West University (South Africa) where he is Associate Professor of Economic History