Speculators, Fiscal Foundations and Economic Reorganization, 1900-1910

Tinashe Nyamunda

The last article [published on May 18, 2020] examined, in part, the way that the colonial monetary system in early colonial Zimbabwe’s legal foundations were borrowed from the British Cape colony’s legislation (part of present-day South Africa). It also examined the earliest forms of state formation in 1898 when the Legislative Council (LegCo) was established. Among the first pieces of legislation tabled by the LegCo was an Ordinance to Regulate Banking and Note Issue designed to make way for the establishment of a State and Public Bank.

This had been necessitated by coin shortages which dislocated business. But even as pseudo currencies were used, another challenge was how to coerce Africans to provide wage labour. Through compulsory taxation, two tier pricing in which African products were purchased at a lower price and the beginning of land dispossession; the process of proletarianisation had started. استراتيجية الروليت في التعليم The LegCo needed to secure a functional and stable monetary system. For this, a State and Public Bank would have been the answer. This however required British Royal Assent, the response of which was stalled.

Between 1890 and 1900, the BSAC had hoped to find a Second Rand, that is, a mining industry that would be as profitable as the Witwatersrand mines had been since their discovery of gold in 1886 in the Transvaal Republic (part of present day South Africa). By 1900, the Second Rand had not materialised in Zimbabwe, in part, because of the low yielding reefs that made up part of the country’s geology. Instead, the BSAC had sustained itself through false reporting of the capacity and promise of the colony’s mining industry and thus facilitated much speculation on the London Stock Exchange.

On top of an unsustainable mining economy, floating on speculative interests, the Chimurenga/Umvukela (1896-1897) and Anglo Boer wars (1899-1902) exacerbated the economic downturn. By 1900, the nascent colony was facing a number of economic challenges even as coin shortages worsened. The speculative bubble burst as it became increasingly clear to BSAC shareholders that, compared with the Rand, gold would never be found as easily or in large volumes in Southern Rhodesia because of the nature of its geology.

Despite the challenges the colony faced, it resolved to achieve three main objectives. The first was to create a fiscal framework to govern the colony. Africans were taxed and revenue generated from other economic activities. On the basis of the Royal Charter, the BSAC was tasked with the burden of administration and required to construct infrastructure such as roads and railways. But to consolidate the revenue collected, a Treasury Department was created in 1903. The Treasury Department was the forerunner of what would become the Ministry of Finance.

The establishment of the Department of Treasury laid the foundations of fiscal management, but revenue collection continued to worsen as coinage shortages persisted. This was exacerbated by limited banking activities; there were only two commercial banks in the colony, the Standard Bank established in 1902 and The Bank of Africa which began operations in 1895. But these banks had very few branches in the country and were exclusive, catering mainly to a limited number of white settlers in the main economic centers of Harare and Bulawayo. They did not have reach in more remote areas. Moreover, an important source of taxation revenue – the Africans, did not have access to banking facilities whatsoever.

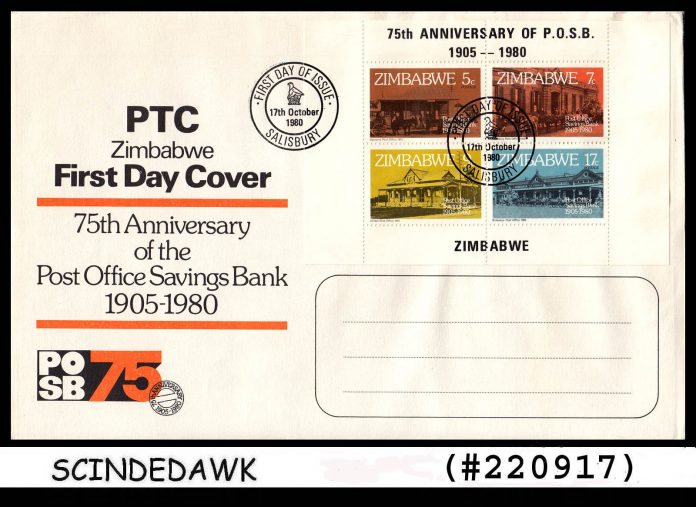

While setting up Treasury consolidated the basis for the development of state fiscal management, monetary arrangements needed to be resolved. Apart from continuously trying to secure more coin deliveries from Britain and South Africa, another attempt at resolving this was to facilitate banking inclusion in which Africans could also access banks. Not just those in the emerging economic capitals of Salisbury and Bulawayo, but also those, and other whites who settled in remote areas. To try and facilitate this, the LegCo passed a Bill in 1905 that led to the establishment of a Post Office Savings Bank (POSB).

The POSB had been established in 1886 in Britain to facilitate banking inclusion of low-income groups. The one formed in Southern Rhodesia was modeled on the British one. It was established to encourage thrift (savings) by low income white people and avoid the hemorrhage of money from the colony which already faced coin shortages. While the bank was established primarily to encourage savings by whites, especially civil servants such as the British South African Police and facilitate savings certificates for retirement, it did not necessarily discourage black people from using the bank. Also, because the Post Office delivered mail in remote areas, it could easily provide banking facilities in those areas.

However, because of continued coin shortages, banditry, and logistical challenges, the POSB registered limited successes. Over time, the POSB would increasingly take on the character of becoming the most accessible bank for low income groups thus earning its depiction as a people’s bank. In the early years however, its limited impact meant that specie shortages persisted.

The problems of banking exclusion have persisted till this day. Some modern forms of innovation that attempt to incorporate the unbanked include mobile money platforms such as MPESA in East Africa and Ecocash in Zimbabwe, among others. However, although requiring less stringent requirements than banks, they have a host of challenges, such as high transaction costs and other logistical challenges. The problems of banking exclusion can be traced back to the early days of colonial monetisation and the ways in which it was designed to cater for the imperial needs at a grander level, white settler convenience at local level and the subjugation of African enterprise in a process that would reduce them to mere providers of wage labour.

The establishment of the Department of the Treasury in 1902 and the POSB in 1905 took place at a time when the mining industry was facing a severe downturn. The BSAC, which had colonized Rhodesia on behalf of Britain, also had to make a fortune from mining. It realised that it needed to shift focus to make the colony economically self-sufficient and try to generate dividends for the shareholders of the BSAC. This was especially important because, up to 1907, the British had stalled on approving the Ordinance on Banking and Note Issue that had been tabled in 1898 at the establishment of the LegCo. In that same year, the Bill was thrown out by the British government and the State and Public Bank never materialized.

The LegCo’s reasons for wanting to establish the State and Public Bank was to facilitate the minting of coins and issuing of notes in the colony to ease the problem of shortages. In effect, modelled on the Bank of England, it would have functioned like a central bank in the colony. But at that time, no central banks in British African colonies had been established, let alone currency boards.

In fact, the first currency board among British colonies was only established in West Africa (headquartered in Nigeria) in 1912. The South African Reserve Bank would be established in 1919, and Rhodesia would only get a currency board in 1938. The reason why Britain refused to allow its colonies to have any forms of monetary institutions such as the State and Public Bank was that it wanted to ensure that trade was conducted in a currency of its own choosing that it controlled.

This ensured that Britain could continue to extract commodities from the continent on the basis of a currency that it controlled and prices that it determined. So, despite settler attempts at currency autonomy, Britain would never have agreed as this would compromise its imperial enterprise, which was largely connected to the use of sterling. This left the settler whites with little option but to ensure that they derived profit by trading with Britain. Among their strategies was exploiting African labour on farms and mines that produced commodities sold in sterling overseas. The answer lay in forcing Africans to accept this currency, disenfranchising them economically and thus forcing them to work at their enterprises for ultra-cheap labour. In this way, money became a central tool of subjugating Africans to the whims of colonial capitalism.

Gradually, the BSAC turned its focus from a mining-centred economy towards making land productive for white commercial enterprise. They also constructed lucrative railways that ferried commodities from mines and farms towards local economic centres and then towards ports for shipment overseas. The BSAC had secured ownership of the bulk of the country’s land, under the provisions of the 1889 Rudd concession, which Lobengula was tricked into signing, and the Royal charter granted by Britain. Thus in 1908, the company government began parceling land to white farmers, hoping that once it became productive, other white immigrants would want to come and buy land from them.

The BSAC even established their own subsidiaries such as the Rhodesian Mining and Land Company which would later be taken over, after its reorganization in the 1950s, by Tiny Roland who renamed it LONRHO. But among the major challenges that early farmers faced was capital. To try and resolve the challenges, the LegCo used several strategies.

First, the LegCo tried to undermine African farming by setting rock bottom prices for African produce, especially when compared to European produce. This was designed to boost production. Secondly, much of the earlier land had been given to pioneer settlers and members of the British South Africa Police freely in payment of services. Finally, there was a lot of talk about establishing a financial institution to finance white settler agriculture. Even though a Land Bank would only be established in 1912, the LegCo found ways of assisting white farmers.

Among these strategies was forced black labour. Those who would not have paid taxes or been arrested for some other crimes could be sent to work for these farmers for no pay. casinocom So, at various levels, the colonial system was being developed on the basis of primitive capitalism. Ultimately, it was these foundations that laid the scaffolding for further developments in the later parts of the twentieth century.

In conclusion, between 1900 and 1910, coin shortages persisted thus continuing to dislocate business. Attempts to resolve coinage shortages by establishing an equivalent of a central bank in the nascent colony contradicted imperial interests of securing its colonies through a sterling currency network of commodity extraction. As such, the Bill proposing the State and Public Bank in Southern Rhodesia was thrown out. But the LegCo was allowed to create its fiscal foundations, founded on sterling-based taxes through the establishment of the Department of the Treasury. And to cope with coin shortages and to encourage thrift, such organizations as the POSB were established. However, the crucial development was the entrenchment and growth of the colonial economy through the reorganization of the agricultural industry. Ultimately, as the sectors of the economy expanded, settlers secured themselves on the land with the help of the state while Africans were further disenfranchised politically and economically in this process. At the centre of all this was how money was used to transform them into providers of cheap labour while their means of production was systematically taken from them.

- Tinashe Nyamunda is with the African Modernities Past and Present (AMPP) research group at North West University where he is Associate Professor in Economic History. رهان الان

Was really waiting for the second edition after reading the first one and l must say this is a must read article that narrates Zimbabwe’s historical events and the monetary issues in a non-vexatious way. Very interesting facts being unfolded….. looking forward to the third edition.

Very concise and informative indeed. Thank you Prof Nyamunda.

Thank you once again for another interesting piece on the history of currency in Zimbabwe. I was specifically fascinated by the history of mobile banking via the POSB. History surely repeats itself.

Is it possible to know if Africans received the same banking privileges as the low income whites in the POSB? I’m asking because it was referred to as the people’s bank. This question includes the differences in interest rates and dividends offered by the savings bank.

My other question is the impact of this Savings bank to the colonial capital market. In Britain when Savings banks were created, they expanded the capital market and many businesses benefited from them as they received money from low income earners and provided it as credit to entrepreneurs. So, before it’s failure, did the colonial savings bank contribute to the economy in this manner?

With that being said, I enjoyed your op-ed.