Jonathan Waters

BRITAIN had introduced daylight saving during World War I ostensibly to save coal. While this has been found to be a fallacious argument given the same number of daylight hours remain regardless, there was a good deal of support for the move and most British territories and colonies that were contributing to the war effort introduced similar legislation to the British Summer Time Act of 1916 in the years that followed.

Since colonisation by the British South Africa Company in 1890, time had been a variable concept. Few settlers owned wristwatches and much work on the farms and mines was aligned to sunrise. To provide some uniformity, a midday gun was fired in most towns on a daily basis. However, it was the coming of the railway line in 1897 that “brought time” to the country as the efficient running of the service required a timetable to be stuck to.

The debate on daylight saving first came before the Southern Rhodesian Legislative Council in April 1917 and discussion was broadly in favour of the Daylight Saving Ordinance as it would improve “the health and recreation of the community”, particularly in the urban areas. But Marandellas MP John McChlery said he did not think that “the people of this country led very strenuous lives, so the question of recreation did not weigh with him very much.”

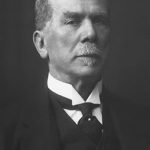

The Daylight Saving debate produced no hard positions, and this led Treasurer Francis Newton (on left) to state – to much laughter in the Legislative Council – that he had been reminded of John’s message to the Laodiceans in Revelations (“I wish that you were cold or hot”)

The Daylight Saving debate produced no hard positions, and this led Treasurer Francis Newton (on left) to state – to much laughter in the Legislative Council – that he had been reminded of John’s message to the Laodiceans in Revelations (“I wish that you were cold or hot”)

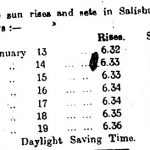

While December 22 may be the longest day in terms of sunlight hours in the southern hemisphere and June 21 the shortest, the sun sets at its latest point (in Harare) around January 20 at 6:37pm in the evening. The day is still shortening by around half a minute because dawn is getting later at a faster rate than dusk.

In early June, the process is reversed as the sun starts to set later, but sunrise is also still taking place later, so the day is getting shorter, albeit by seconds. The sunset takes place no earlier than 5:27pm in early June, and the difference in sunlight hours between June 21 and December 21, which is known as the “diurnal range”, is only 2 hours and 9 minutes.

Compared with the European Summer, there is not much to play with. Given the sun sets at its latest point in January, the general prognosis in late 1919 was in favour of a three month trial. There had been a plan to introduce the Ordinance in 1918, but owing to “the continuation of war conditions and the opposition of one or two of the outside districts, the government decided to defer taking action,” the Rhodesia Herald reported.

In November 1919, the business communities of Bulawayo and Salisbury got behind the proposal for the trial and in its editorial of December 2, 1919, the Herald boldly declared: “Of course we are ready to recognise that the introduction of Daylight Saving for the last three months of the current summer season is the nature of an experiment, but we have little doubt that the results will prove so satisfactory in future that all parties directly concerned will demand that the community shall be afforded the extra hour of daylight from October 1st to March 31st.”

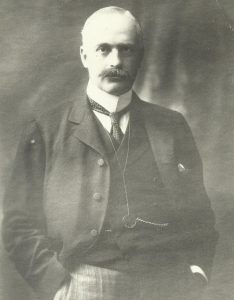

The Administrator Sir Drummond Chaplin (on left) issued an extraordinary Government Gazette on January 1, announcing the clocks would go forward from midnight on January 4 to March 31

The Administrator Sir Drummond Chaplin (on left) issued an extraordinary Government Gazette on January 1, announcing the clocks would go forward from midnight on January 4 to March 31

Opposition to the experiment started to become more notable in the run up to the introduction. Jacob Smit, a store owner who was to go on to be finance minister in the 1930s, said he thought the bill was altogether unnecessary and was “due to the local Chamber of Commerce, who, unable to invent new sources of shining as lawmakers, are content to ape the results of the deliberations in the House of Commons, to prove their political worth.”

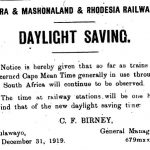

After the clocks went forward, the realities of the change and certain inconveniences became apparent. The railways were against the change and did not bother putting their clocks forward nor changing their timetables, saying they had to “conform with the times laid down for connections with the Union Railways.

After the clocks went forward, the realities of the change and certain inconveniences became apparent. The railways were against the change and did not bother putting their clocks forward nor changing their timetables, saying they had to “conform with the times laid down for connections with the Union Railways.

Smit’s store on Baker Avenue, now Nelson Mandela, where the Bata store stands (the warehouse just beyond is the site today of Harvest House and note the Dutch Reformed Church in the background, which still stands today on Samora Machel Avenue). “Some people seem to think it is necessary to prove their loyalty to the Old Country, even to the point of making themselves ridiculous,” Smit said in his stand against Daylight Saving.

Smit’s store on Baker Avenue, now Nelson Mandela, where the Bata store stands (the warehouse just beyond is the site today of Harvest House and note the Dutch Reformed Church in the background, which still stands today on Samora Machel Avenue). “Some people seem to think it is necessary to prove their loyalty to the Old Country, even to the point of making themselves ridiculous,” Smit said in his stand against Daylight Saving.

“TD” wrote to the Herald that “the term ‘Daylight Saving’ is not only inappropriate but absolutely misleading, as not only does the Ordinance fail to save us any daylight whatsoever, we shall for some months to come daily be losing a portion of our daylight given the earlier sunset. The Ordinance in question should have been termed ‘The Incorrect Time Ordinance’,” he said.

“TD” wrote to the Herald that “the term ‘Daylight Saving’ is not only inappropriate but absolutely misleading, as not only does the Ordinance fail to save us any daylight whatsoever, we shall for some months to come daily be losing a portion of our daylight given the earlier sunset. The Ordinance in question should have been termed ‘The Incorrect Time Ordinance’,” he said.

In Que Que, the “daylight saving racket” was “universally unpopular”, the Herald reported on January 20. “The whole thing is a farce and is a very much lopsided business. Travellers by the railways find that when, after hurrying to catch the four o’clock train they have a good hour to spare, as the railway company is unable to put the new timetable into operation on account of the Cape connections.”

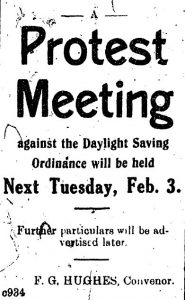

Early surveys had claimed as much as 25% would be saved on the lighting bill, but this is erroneous as the hours of darkness do not change regardless. There were complaints from parents that the trial was depriving children of two hours of sleep every night. But it was to be a Salisbury resident – FG Hughes – who was to lead the campaign for the abandonment of the experiment. A petition was circulated and gathered 980 signatures against Daylight Saving with only 145 in favour.

At a public meeting on January 26 arranged by Hughes – where it was noted there was not a single well-known citizen in the crowd – builder John Coull heaped the blame on the Herald for the introduction: “The only person who wanted it was the editor of our dear old rag. He had nothing else to say; he wrote a leader and then a sub-leader on daylight saving. I did not know until then that anyone took our editor seriously. I never did, and I don’t intend to now.”

At a public meeting on January 26 arranged by Hughes – where it was noted there was not a single well-known citizen in the crowd – builder John Coull heaped the blame on the Herald for the introduction: “The only person who wanted it was the editor of our dear old rag. He had nothing else to say; he wrote a leader and then a sub-leader on daylight saving. I did not know until then that anyone took our editor seriously. I never did, and I don’t intend to now.”

The Herald was unabashed in its support and called for “the authorities and the public to take a firm stand against being stampeded into a reversal of policy unless the grounds for such a reversal are reasonable and tangible.” The editorial noted it had published the letters of many of the critics, including that of Reverend TCB Vlok, who said he had contracted malaria due to his lack of sleep!

But the government quickly capitulated before the movement gained any further support. On Saturday January 31, less than a month into the trial, the Administrator Drummond Chaplin issued an Extraordinary Government Gazette: “Under and by virtue of the power conferred by Section 1 of the ‘Daylight Saving Ordinance, 1917, I hereby amend Government Notice No 587 of 1919 by cancelling the words ’31st March 1920’ and substituting therefore the words ‘1st February, 1920.”

The Herald was a little less boisterous after the revocation, reporting that: “The new system did not work so well as anticipated, and strong representations were made in favour of a reversion to standard time. It is understood that nearly all the public bodies who supported the movement last year found reason to change their attitude and acquainted the authorities of this fact.”

Around the country, the cessation of daylight saving was welcomed, being received “with relief” in Umtali. In the Midlands, it was reported: “Official instructions for putting back the clock were received here Saturday noon and it did not take long for the news to spread all through the town. Daylight saving was by no means welcomed in Gwelo and general satisfaction is expressed at its being cancelled.”

For the next generation, the daylight saving movement died at that point, although it must be said that many mines operated on “mine time”. This is what had complicated matters at Umvuma in 1920 – one of the major urban centres of the time. The General Manager of Falcon Mines had complained that daylight saving had proved inconvenient, as mine time was half an hour behind post office time and half an hour ahead of railway time, thereby creating three time zones in the town!

South Africa observed two periods of daylight saving in World War II in the summer seasons of 1942 to 1944 and the Rhodesians toyed with the idea but it was never implemented. In the early 1950s, the shortage of coal saw the debate revived. priligy generique avis Municipalities discussed proposals, but they came to nothing. Perhaps as a result of the large number of British immigrants, the debate came up again in the late 1950s and in February 1959, parliament agreed “in principal” to introduce daylight saving.

The argument again was “better health” and fewer road accidents given most happened in the early evening. But it was never implemented. There are very few African countries that observe daylight saving today, mostly Atlantic islands tied to Portugal and Spain. Namibia conducted “winter time” from 1994 until 2017 as part of measures to allow children to get to school in daylight hours, but clocks in the Caprivi region were not changed. The legislation was repealed in August 2017.