By Jono Waters

The Spanish Flu epidemic struck Rhodesia in early October, 1918, being introduced into the country by passengers arriving from South Africa by train. It spread quickly in all the urban centres before making its way into the districts. It must be remembered the World War I was still underway, and the formidable German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who kept the Allied forces at bay in East Africa for most of the war, had chillingly just invaded Northern Rhodesia.

The Spanish Flu epidemic struck Rhodesia in early October, 1918, being introduced into the country by passengers arriving from South Africa by train. It spread quickly in all the urban centres before making its way into the districts. It must be remembered the World War I was still underway, and the formidable German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who kept the Allied forces at bay in East Africa for most of the war, had chillingly just invaded Northern Rhodesia.

Given the difficulty of collecting statistics of black deaths in rural areas at the time, it is estimated that between 2% to 3% of the black population of 825 000 at the time perished – that is, around 20 000. The death toll among the European population was 516, out of a population of 30 200, which was equivalent to 1.7% of the population.

Within days of the first cases being reported, the authorities banned gatherings, closed schools, places of entertainment and churches as well as ordering shops to close at 1pm, which was a move aimed more at releasing volunteers to work among the sick. ivermectina valor doctor simi In Salisbury and Bulawayo emergency hospitals and quarantine stations were set up, in addition to soup kitchens.

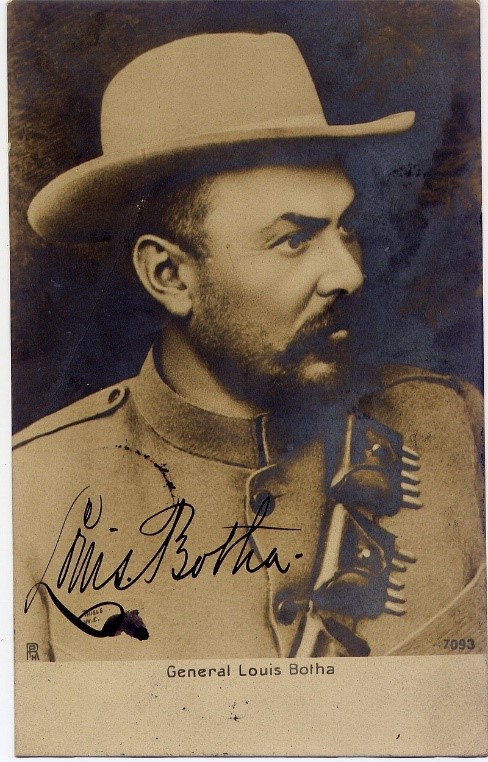

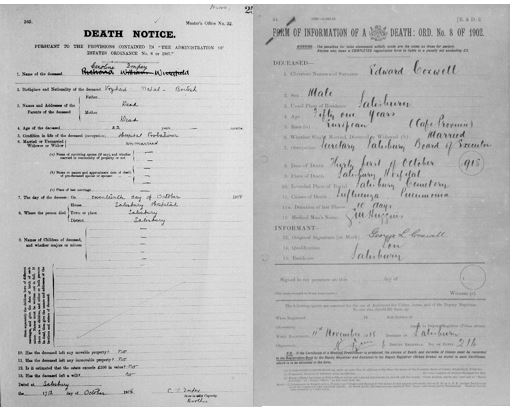

Salisbury and Bulawayo reported the first Europeans deaths on October 17, a nurse Caroline Impey in the capital and the Acting Sheriff of Bulawayo, Mr LJ Champion. But the most high profile death was on October 31 – that of Edward Coxwell, the former mayor, aged 51, who had also been in charge of the Salisbury Board of Executors. how to treat a dog with ivermectin toxicity

Early closing hours on shops lasted from October 21 to November 7, 1918. Schools reopened on November 17, but pupils were required to report with “a certificate that there has been no contact with infectious disease”. Many thought the move was premature and 85% of scholars opted to stay away. The Rhodesia Herald commented at the time: “These figures are eloquent of our contention that, with the best desire in the world, parents have either not been able to comply with the regulation referred to, or have no intention of sending their children to school until they are assured the danger of infection is over.

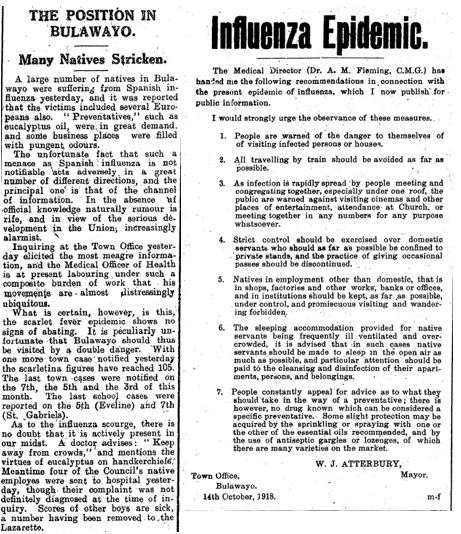

Looking back a year later, the Mayor George Elcombe said: “Residents in town nobly responded to the call to assist in nursing the sick and distribute food where required. Business was practically at a standstill, many business houses being closed entirely and all the stores closed at midday for upwards of three weeks, thus releasing their staffs to assist in care for the unfortunate friends and neighbours. Free inoculation was provided by the council and every step was taken to stamp out the disease and relieve the suffering. mectizan merck In spite of all our efforts, the mortality was very heavy. Since the epidemic we have carefully watched fora recurrence, but so little is at present known of the disease that it is practically impossible to take precautionary measures.”

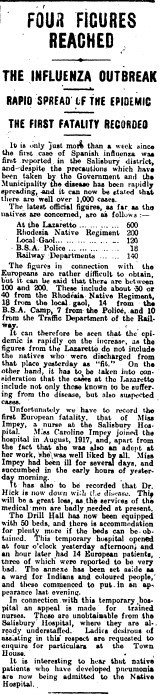

Bulawayo was just getting over a scarlet fever epidemic when the first case was reported on October 9 among railway workers, as shown in this Chronicle article from October 11, 1918. As with Salisbury, the Drill Hall was used as an emergency hospital with for whites, while the hall at the municipal brewery in the township – today Makokoba – was converted into a hospital for blacks

| In a History of Southern Rhodesia, Lewis Gann said:

“The great influenza epidemic hit the country just as the Kaiser’s armies were tottering to defeat. People found this new kind of plague much more terrifying in some aspects than the war itself. ‘Spanish Influenza’ affected most of the world, but the virus may somehow have become more virulent on its passage through Africa, and for a time, Southern Rhodesia was struck numb. Shops closed, transport firms stopped doing business, and life stood still, as the ‘flu’ claimed victim after victim. Africans suffered even more severely than white men, especially in crowded locations and mining compounds, whilst doctors lacked any effective remedy with which to fight back. Stricken people would collapse in the streets, and experts estimate the total death rate in the countryside at about 2 to 3 per cent. Native Commissioners organised African teachers, messengers, and policemen into groups to help. In the towns, there was a momentary feeling of panic, but the municipal authorities acted with commendable initiative and many volunteers came forward to act as nurses. The Salisbury Drill Hall was hurriedly turned into an emergency hospital and Boy Scouts and girls hardly out of school tried to cope with patients in their death throes. Many doctors were struck low, but others, including Andrew Fleming, the Medical Director, and Godfrey Huggins, a young English surgeon straight back from the war, remained on their feet day and night, in some cases signing death certificates without even getting time to inspect the victims. When news of the Armistice on November 11 came from Europe that the war was over, none felt like celebrating for death was still stalking the streets. In mid-November 1918, however, the pestilence, after about five weeks, at last showed signs of abating and life began to return to normal. The crisis also did some good. In Bulawayo, the more flourishing and progressive settlement in the country, the plague resulted in more effective measures to prevent African overcrowding and better supervision of native eating houses. Salisbury for its part began to agitate for better hospital facilities and more effective public health laws. The epidemic left many children without parents, and sometime after the Rhodesia’s Children’s Home opened its doors to care for homeless white children, who – unlike African orphans – could not call on the assistance of extended family groups.” |

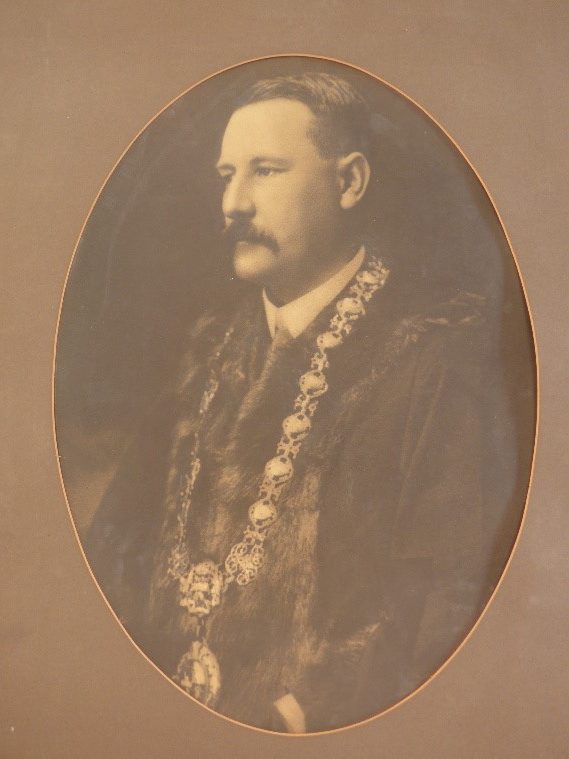

The most high-profile death in Salisbury was that of former Mayor Edward Coxwell, left, who served two terms (1905-1906 and 1913-1914) and has a street in Milton Park named after him, while General Louis Botha, the 1st Prime Minister of South Africa died on August 27, 1919

In Salisbury out of 320 white admissions to the Drill Hall (now Makumbe Building) and General Hospital, 49 people died, whilst 160 Africans perished out of the 1 067 people treated at the ‘Lazaretto’ (quarantine station) at what is the Harare showgrounds today. It is said the belts of gum trees that used to flourish in the showgrounds mark the graves of over 200 victims

In Salisbury out of 320 white admissions to the Drill Hall (now Makumbe Building) and General Hospital, 49 people died, whilst 160 Africans perished out of the 1 067 people treated at the ‘Lazaretto’ (quarantine station) at what is the Harare showgrounds today. It is said the belts of gum trees that used to flourish in the showgrounds mark the graves of over 200 victims

Death notice of the first Salisbury casualty, nurse Caroline Impey, who died aged 22 on October 17, 1918. Coxwell’s death notice shows he had been ill for 10 days before he died.

The Mother of all Pandemics – From The Week

The coronavirus outbreak is sometimes compared to the Spanish flu of 1918 – the most deadly pandemic in human history

Where did Spanish flu originate?

It first erupted in the spring of 1918, but its origin is still not clear; it certainly was not Spain. There had been earlier outbreaks in the US and Western Front, but that information was kept out of the newspapers, to avoid damaging wartime morale. The Spanish, who were neutral during the war, reported an outbreak – hence this is how the name came about. The original source may have been Camp Funston in Kansas, where the first cases were recorded in March 1918; or the British Army’s vast transit camp in Etaples in northern France; or Shanxi province in China, where there was a flu like epidemic in 1917. At any rate, by mid-April 1918 it had reached the Western Front. It came in three waves: a second more deadly variant of the disease struck Europe, the US and Africa in August; there was a third outbreak in 1919.

How many people died of Spanish flu?

Incubated in barracks and carried around the world by soldiers and sailors, it infected an estimated 500 million people, nearly a third of the global population. Estimates vary, but it is thought that 50 million people died – several times the number killed in World War I – mostly between September and December 1918. In France, 400,000 people succumbed to the disease, in the US, more than half a million. It was truly global, affecting every continent except Antarctica: Iran, Brazil, Ghana and Japan to name a few, were badly hit. In Western Samoa, 22% of the population died. Even harder hit were the Alaskan Inuit, with an overall death rate of 25% to 50%. Asians died in the greatest numbers. India lost an estimated 17 million people – about 5% of its population.

What were the symptoms?

It began, like normal flu, with a cough, headache, fever and aching limbs. For most, it stopped there, but for some, it took a virulent form, often killing them in 24 hours. The virus targeted the cells of the lungs and airways and filled them with blood and fluid; the lips, ears, face, fingertips, and toes would turn blue – a sign of ‘cyanosis’, or oxygen deprivation. In some cases, victims turned purple, or even black. People died struggling to clear their airways of what one doctor called “a blood-tinged froth that sometimes gushed from their nose and mouth.”

Broadly speaking, the Spanish flu killed around 10% of those that were infected, much higher than coronavirus, which it is said is four times more contagious, but only twice as deadly as the common cold.